Have you ever been curious about building a video game ? Do you have an idea about how web sockets work but can't utilize that knowledge to create something ? If so, join me as I try to build a small game on the web and hoping to learn a thing or two along the way.

What game are we building ?

We're building a game called Tic-Tac-Toe. For the uninitiated, Tic-Tac-Toe is a game for two players who take turns marking the spaces in a three-by-three board (grid) with X or O. The player who succeeds in placing three of their marks in a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal row is the winner.

A simple game. But the moment we start thinking about representing/storing the game state and broadcasting changes in the game state to players and spectators, the project starts looking a little bit more challenging.

Breaking things down

I'm going to split the game into two projects: a server and a client. As you may have guessed, most of the magic will happen on the server. And so most of the focus of this article is going to be on the server and I'll create a very minimal client that just proves that every thing works together. Keep in mind that I won't be going through every single line of code in an attempt to be as concise as possible.

Initial server setup

To start we need to setup a node project with the TypeScript compiler, environment variables, .gitignore, and automatic restart on change. Thankfully you won't have to do all of that manually, you can clone the starting boilerplate here.

Next we need to install the dependencies needed:

npm i socket.io uuid lodashWe'll be using socket.io, as it allows us to focus on the bigger picture and not have to worry about the low level details of establishing and maintaining WebSocket connections.

The state

The first thing we need to think about is what state do we need to store ? Since we support multiple rooms, each room can have multiple participants: 2 players and any number of spectators in case of Tic-Tac-Toe, we need a place to store each room and it's respective state. A Map is an ideal data structure for that. For the sake of simplicity, we'll store everything in one object in memory on the server:

const TheBossObject = {

xo: {

name: 'Tic Tac Toe',

rooms: new Map<string, XORoomState>(),

},

};Before we start thinking about the particular rules and logic of Tic-Tac-Toe we need to implement a data structure that abstracts the state of any game room. There are a few aspects that are common in most games:

abstract class RoomState {

protected connectedPlayers: Array<Player> = [];

protected abstract gameState: any;

protected status: 'notReady' | 'ready' | 'inProgress' | 'done' = 'notReady';

protected minPlayers: number;

protected maxPlayers: number;

constructor(minPlayers: number, maxPlayers: number) {

this.minPlayers = minPlayers;

this.maxPlayers = maxPlayers;

}

}We implement an abstract class called RoomState. In it we have the array of connected players, the status of the current match, and minimum and maximum number of players that can join the room. These encompass the state of any room of potentially any game, not just Tic-Tac-Toe. We will have to implement the gameState class property in the subclass as this will store the specific board information of Tic-Tac-Toe game.

Next we need to define a few methods that encompass basic aspects of a match in a room.

isReady() {

if (this.connectedPlayers.length === this.minPlayers) {

this.status = "ready";

return true;

}

return false;

}Almost every method in the RoomState class is going to perform an operation and return a boolean expressing the success of that operation. This pattern will help us perform less verbose checks and reduce clutter in the socket.io code. In this example, isReady is going to check if the number of connected players is equal to the minimum number of players and if so, it changes the room status to "ready" and return true. This method will be used a lot in defining other methods in the class.

Next we need a method that allows us to start the match in the room.

start() {

if (this.status === "ready") {

this.status = "inProgress";

return true;

}

return false;

}We'll need two methods to add and remove players from the room.

addPlayer(player: Player) {

if (this.isJoinable()) {

this.connectedPlayers = this.connectedPlayers.concat(player);

this.isReady();

return true;

}

return false;

}

removePlayer(socketID: string) {

this.connectedPlayers = this.connectedPlayers.filter(

(player) => player.socketID !== socketID

);

this.isReady();

}Of course we won't be defining every method in this abstract class, some methods will need to be implemented by the subclass.

abstract isFinished(): boolean;

abstract reset(): boolean;

abstract move(...args: any): boolean;Next we need to write the subclass that extends the abstract class RoomState in a way that reflects the specific rules of the Tic-Tac-Toe game. Let's call it: XORoomState.

First let's define a name for each slot in the board:

export type XOSlotName = '0-0' | '0-1' | '0-2' | '1-0' | '1-1' | '1-2' | '2-0' | '2-1' | '2-2';Next we define the possible values a slot can have:

type XOSlotState = undefined | null | 'X' | 'O';After that we define the main properties of the sub-class, XORoomState:

class XORoomState extends RoomState {

protected boardState: {

currentTurn?: Player;

slots: {

[key in XOSlotName]: XOSlotState;

};

};

protected playerX?: string;

protected playerO?: string;

protected result?: 'X' | 'O' | 'DRAW';

private static winningSlots: Array<Array<XOSlotName>> = [

['0-0', '0-1', '0-2'],

['1-0', '1-1', '1-2'],

['2-0', '2-1', '2-2'],

['0-0', '1-0', '2-0'],

['0-1', '1-1', '2-1'],

['0-2', '1-2', '2-2'],

['0-0', '1-1', '2-2'],

['0-2', '1-1', '2-0'],

];

constructor() {

super(2, 2);

this.boardState = {

slots: {

'0-0': null,

'0-1': null,

'0-2': null,

'1-0': null,

'1-1': null,

'1-2': null,

'2-0': null,

'2-1': null,

'2-2': null,

},

};

}

}Here we define the board state as an object that contains the current player and the state of each slot. We also define playerX and playerO properties, which will hold the socketID of the players for each role. We also define the result. And last but not least we define the winningSlots, an array that holds combinations of winning moves.

Keep in mind that whenever a client establishes connection with our server, socket.io will assign it a unique socketID. We'll be using that throughout the code to uniquely identify our users.

Since there some particular rules to adding or removing players in a match of Tic-Tac-Toe, we need to reimplement the addPlayer method.

addPlayer(player: Player) {

const result = super.addPlayer(player);

if (!result) return false;

if (!this.playerX) {

this.playerX = player.socketID;

} else if (!this.playerO) {

this.playerO = player.socketID;

}

return true;

}As you can see, we call the addPlayer method from the super class. And depending on the success of that operation, we'll assign the player that just joined "X" or "O" then return true.

Once both players are in the room, we need a way to assign the current turn randomly to one of them before we start the game.

start() {

if (this.status !== "ready") return false;

this.boardState.currentTurn =

this.connectedPlayers[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.connectedPlayers.length)

];

this.status = "inProgress";

return true;

}Now that the game started, we need to handle player movement. And since Tic-Tac-Toe is turn-based, we need to only allow movement to the player whos socketID equals the currentPlayer's socketID We also make sure they're making a move in an empty slot. Then, we fill the slot based on the player's role (X or O). Lastly, we switch turns to the other player in the room.

move(slot: XOSlotName, socketID: string) {

if (this.status !== "inProgress") return false;

if (this.boardState.currentTurn?.socketID !== socketID) return false;

if (this.boardState.slots[slot]) return false;

if (this.playerX === socketID || this.playerO === socketID) {

this.boardState.slots[slot] = this.playerX === socketID ? "X" : "O";

this.boardState.currentTurn = this.connectedPlayers.find(

(player) => player.socketID !== socketID

);

this.isFinished();

return true;

}

return false;

}After all of that we need to check if the match is over. That's where the isFinished method comes into play.

isFinished() {

if (this.status === "notReady" || this.status === "ready") return false;

if (

XORoomState.winningSlots.find((slots) => {

const xWins = slots.every(

(slot) => this.boardState.slots[slot] === "X"

);

const oWins = slots.every(

(slot) => this.boardState.slots[slot] === "O"

);

if (xWins || oWins) this.result = xWins ? "X" : "O";

return xWins || oWins;

})

) {

this.status = "done";

return true;

}

if (compact(Object.values(this.boardState.slots)).length < 9) return false;

this.status = "done";

this.result = "DRAW";

return true;

}It might look a bit gnarly. But it's actually quite simple. To decide whether or not the match is finished, we first make sure the match has started. Then, we check the board against our predefined winning slots. If the board contains any combination of winning slots, we check if that combination belongs to one player. If that's true we declare the game a win for that player. If not we check if the board doesn't have any empty slots. We use lodash's compact method which filters an array of all falsy values. If that's true we declare the game a draw.

That was a lot. And we haven't even gotten into any WebSockets or Realtime shenanigans yet 😅. The good news is that we're done with the most difficult part of this endeavor. In an online game (or any game for that matter), managing the state can be extremely messy and challenging. But since we've put a lot of thought and effort into how to represent it and the operations that can be done to it, our actual sockets code is going to be very simple. As it will just involve mapping the operations we just defined in our XORoomState.ts class into events that are broadcasted bi-directionally between the server and clients. And since we'll be using socket.io, we won't even have to worry about the low level details of that bi-directional communication.

Events, events everywhere

We know what our state look like. We've defined the operations that can be done on it. But where exactly is this state going to be stored ? What's our source of truth ? It can't be the client. Because then each client would have it's own version of the state and syncing that would be a nightmare. The optimal approach here is to make the server a single source of truth. With that constraint, we don't have to worry about conflicting versions of the state from multiple clients. Clients just emit an event with a minimal payload. The server then handles that event and then emits the new version of the state to all clients.

Here's how creating a room would work:

Here's how making a move would work:

Keep in mind that each operation would generally include 2 events. An event the client emits to the server whenever it wants to do an operation. Another event the server emits whenever the state changes. Again, the server is the single source of truth here. So no client would be sending new versions of the state. The client will only be allowed to send an event with minimal payload. For example when a player makes a move, they won't send the whole board. They will only send the slot they want to make a move on. The server will then decide whether that was a valid move or not and only emits a new state then.

With that in mind let's start coding by initializing our socket.io server in index.tsfile.

import { createServer } from 'http';

import { Server as SocketIOServer } from 'socket.io';

const http = createServer();

const io = new SocketIOServer(http, {

cors: {

origin: 'http://localhost:3000',

methods: ['GET', 'POST'],

},

});

const PORT = 3002;

http.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`listening on *:${PORT}`);

});Since we're developing locally, we only need to allow localhost:3000 to communicate with our server. This is where our client web app is going to live.

Next we create a namespace for our game.

const xoNameSpace = io.of('/xo');Creating a namespace isn't really needed in our case. It just makes the code for the game contained. This will allow us to potentially host more than one game in one socket.io server connection. Read the docs to learn more about namespaces.

Now let's define the custom events that are going to be communicated to and from our server.

export const PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT';

export const ROOM_CREATED_EVENT = 'ROOM_CREATED_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_JOINED_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_JOINED_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_LEFT_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_LEFT_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT = 'PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT';

export const BOARD_CHANGED_EVENT = 'BOARD_CHANGED_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_STARTED_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_STARTED_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_RESET_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_RESET_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_RESETED_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_RESETED_ROOM_EVENT';As you can see an event is just a string that's unique in our system. And as discussed earlier, most operations have 2 events. One the client emits, and one the server emits. This allows the frontend to react differently to each event. But for the sake of simplicity, we introduce an event that captures most room state changes. That will greatly simplify our code. So instead of having the list above, we can just work with the following:

export const PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT';

export const ROOM_CREATED_EVENT = 'ROOM_CREATED_EVENT';

export const GAME_STATE_CHANGED = 'GAME_STATE_CHANGED';

export const PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT = 'PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT';

export const PLAYER_RESET_ROOM_EVENT = 'PLAYER_RESET_ROOM_EVENT';Except for room creation, the server will emit the GAME_STATE_CHANGED event when any change occur to the state. That includes players joining, leaving, starting, moving, winning, or resetting the game. This will also simplify the frontend code. As now we only need to listen to a single event once the room is created.

Some events will occur within the flow of the game but won't be emitted by the client even though the server needs to handle them. For example, what if a player leaves the room by closing their browser tab ? Our frontend code won't be able to emit any events then. That's where socket.io's built-in events become quite useful:

- create-room

- delete-room

- join-room

- leave-room

Another basic event is "connection" which is emitted whenever a connection is established between a client and our server. Most of our code will have to live within its listener. As we can only know the socket.id once a connection has been established.

xoNameSpace.on("connection", (socket) => {

....

}Create room

Let's start by supporting room creation. As the docs state: A room is an arbitrary channel that sockets can join and leave. It can be used to broadcast events to a subset of clients. Now whenever a client emits an event that it wants to create a room PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT, we create a room on the server, give it a unique ID, and then emit another event ROOM_CREATED_EVENT stating that room creation has been successful and giving the client the room ID.

xoNameSpace.on("connection", (socket) => {

socket.on(PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT, () => {

const newRoomID = uuidv4();

socket.join(newRoomID);

xoNameSpace.to(socket.id).emit(ROOM_CREATED_EVENT, { room: newRoomID });

});

}It's worth noting that socket.join(roomID) is an upsert operation. It looks for an existing room with that id in the server, if one is found that socket joins that room. Otherwise, it creates a new room then joins the socket to it.

Since we need to keep track of rooms we need to make a new entry in our Map with the new room ID as key and a new XORoomState object as value:

xoNameSpace.adapter.on('create-room', (room) => {

TheBossObject.xo.rooms.set(room, new XORoomState());

});Keep in mind that here we're listening to the built-in adapter event "create-room" not one of our custom events.

Join room

To support joining a room, we need the client to be able to fire an event demanding to join a certain room.

xoNameSpace.on("connection", (socket) => {

socket.on(PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT, ({ room }) => {

socket.join(room);

});

}Then we listen for the built-in event "join-room", take that socketID, add it as a player in the room state, and then emit a GAME_STATE_CHANGED event to the room signaling that a player has joined.

xoNameSpace.adapter.on('join-room', (room, socketID) => {

TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.addPlayer(new Player(socketID));

xoNameSpace.to(room).emit(GAME_STATE_CHANGED, TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.serialize());

});Start a match

After enough players join the room, the client should emit an event to start the match PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT. The server listens to that event and once it gets it, it'll try to start the match using the start method we defined in the XORoomState class. If it succeeds, the server will emit another event signaling to the room that a match has started.

xoNameSpace.on("connection", (socket) => {

socket.on(PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT, ({ room }) => {

const result = TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.start();

if (result) {

xoNameSpace

.to(room)

.emit(

GAME_STATE_CHANGED,

TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.serialize()

);

});

}Player makes a move

After starting the match, players take turns in marking the empty slots on the board. Same pattern applies. The client emits an event signaling that a player wants to make a move, the server handles that by calling a method in the state data structure XORoomState.move, and on success the server emits an event with the new state to everyone in the room.

xoNameSpace.on('connection', (socket) => {

socket.on(PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT, ({ room, data: { slot } }) => {

const result = TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.move(slot, socket.id);

if (result) {

xoNameSpace.to(room).emit(GAME_STATE_CHANGED, TheBossObject.xo.rooms.get(room)?.serialize());

xoNameSpace.to(room).emit(BOARD_CHANGED_EVENT, { socketID: socket.id });

}

});

});With that we're done with the server part of this project✅.

The client

We're going to build a very minimal client using React. I won't go through every line of code here. I'll focus on how we stitch our SocketIO client with our SocketIO server.

Let's start with create-react-app:

npx create-react-app my-app --template typescriptInstall required dependencies:

npm i socket.io-client uuidI won't get into how to setup routing in React as it's beyond the scope of this article but note that we're using react-router-dom for routing and react-bootstrap as our UI library.

To connect to a SocketIO server, we'll need to use the socket.io-client package to create a Socket client object. Since this client object is going to be needed across our component tree, let's start by creating a React context:

import React from 'react';

import { Socket } from 'socket.io-client';

type KnownSockets = {

mainSocket: Socket;

xoSocket: Socket;

};

const SocketContext = React.createContext<KnownSockets | null>(null);

export default SocketContext;Remember the namespace we created earlier in the server ? We now have to connect to it separately.

Let's include our context provider in index.tsx. We'll need to connect to our server using the io function from SocketIO client:

import { io } from 'socket.io-client'

import SocketContext from './contexts/Socket'

const mainSocket = io('http://localhost:3002/')

const xoSocket = io('http://localhost:3002/xo')

ReactDOM.render(

<React.StrictMode>

<SocketContext.Provider value={{ mainSocket, xoSocket }}>

<App />

</SocketContext.Provider>

</React.StrictMode>,

document.getElementById('root')

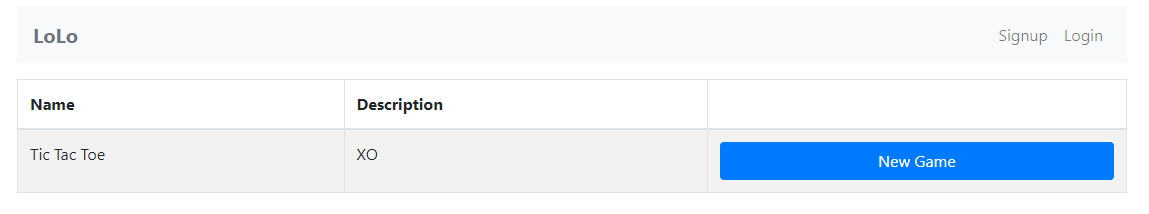

)Next, let's create a home page Home.tsx where the users can create a new room. First we need a button:

<td>

<Button onClick={handleButtonClick} variant="primary" block>

New Game

</Button>

</td>Then we implement our handleButtonClick funciton that will fire a PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT event on click:

const Home = () => {

const history = useHistory();

const sockets = useSockets();

const xoSocket = sockets?.xoSocket;

const handleButtonClick = () => {

xoSocket?.emit(eventNames.PLAYER_CREATE_ROOM_EVENT);

};

return (

...

)

}Lastly we listen to ROOM_CREATED_EVENT event which is emitted by the server signaling that the room was successfully created. We then redirect the user to the room route:

useEffect(() => {

xoSocket?.once(eventNames.ROOM_CREATED_EVENT, ({ room }) => {

history.push(`/g/xo/${room}`);

});

}, [xoSocket, history]);

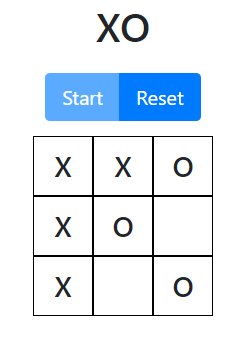

Now let's build our XO.tsx component where the game will take place. By the end it should look like this:

Nothing fancy, but it successfully connects 2 players and let them play the game in real time 👍

Once a user open this page we emit an event to join them to the game room:

const params = useParams<any>();

useEffect(() => {

socket?.emit(eventNames.PLAYER_JOIN_ROOM_EVENT, { room: params.roomID });

return () => {};

}, [socket, params.roomID]);The player also need to be able to start the game so we create a handler function and in it we emit another event:

const handleStartClick = () => {

socket?.emit(eventNames.PLAYER_START_ROOM_EVENT, {

room: params.roomID,

});

};The last operation is when player make a move by clicking on an empty slot on the board:

const handleSlotClick = (slot: string) => () => {

socket?.emit(eventNames.PLAYER_MOVED_EVENT, {

room: params.roomID,

data: { slot },

});

};Finally, we need to listen for game state changes from the server and reflect that in the UI:

const [roomState, setRoomState] = useState<any>();

const sockets = useSockets();

const socket = sockets?.xoSocket;

useEffect(() => {

socket?.on(eventNames.GAME_STATE_CHANGED, (data) => {

setRoomState(data);

});

return () => {

socket?.off(eventNames.GAME_STATE_CHANGED);

};

}, [socket]);All that's left is the UI. Which in our case can be a few divs strung together to make the Tic-Tac-Toe board. First we define a single slot component:

const Slot = ({

slot,

move,

onClick,

}: {

slot: string

move: string

onClick: (...args: any) => () => void

}) => (

<div className={`slot ${slot}`} onClick={onClick(slot)}>

<h3 className="slot_move">{move}</h3>

</div>

)Then we define the entire board:

const XO = () => {

.....

return (

<CenteredContent>

<div className="XO">

<h1>XO</h1>

<ButtonGroup size="lg">

<Button

type="primary"

disabled={roomState?.status !== "ready"}

onClick={handleStartClick}

>

Start

</Button>

<Button

type="success"

disabled={roomState?.status !== "done"}

onClick={handleResetClick}

>

Reset

</Button>

</ButtonGroup>

<div className="slots_container">

<div className="slots_row">

<Slot

slot="0-0"

move={roomState?.boardState.slots["0-0"]}

onClick={handleSlotClick}

/>

<Slot

slot="0-1"

move={roomState?.boardState.slots["0-1"]}

onClick={handleSlotClick}

/>

.....

</div>

.....

</div>

</div>

</CenteredContent>

);

};